Candy-coated chemistry

There’s a real art to making sweets, and a lot of chemistry too…

Sugars are everywhere. They are the building blocks of carbohydrates, the most abundant type of organic molecule in living things. These carbohydrates provide us with energy.

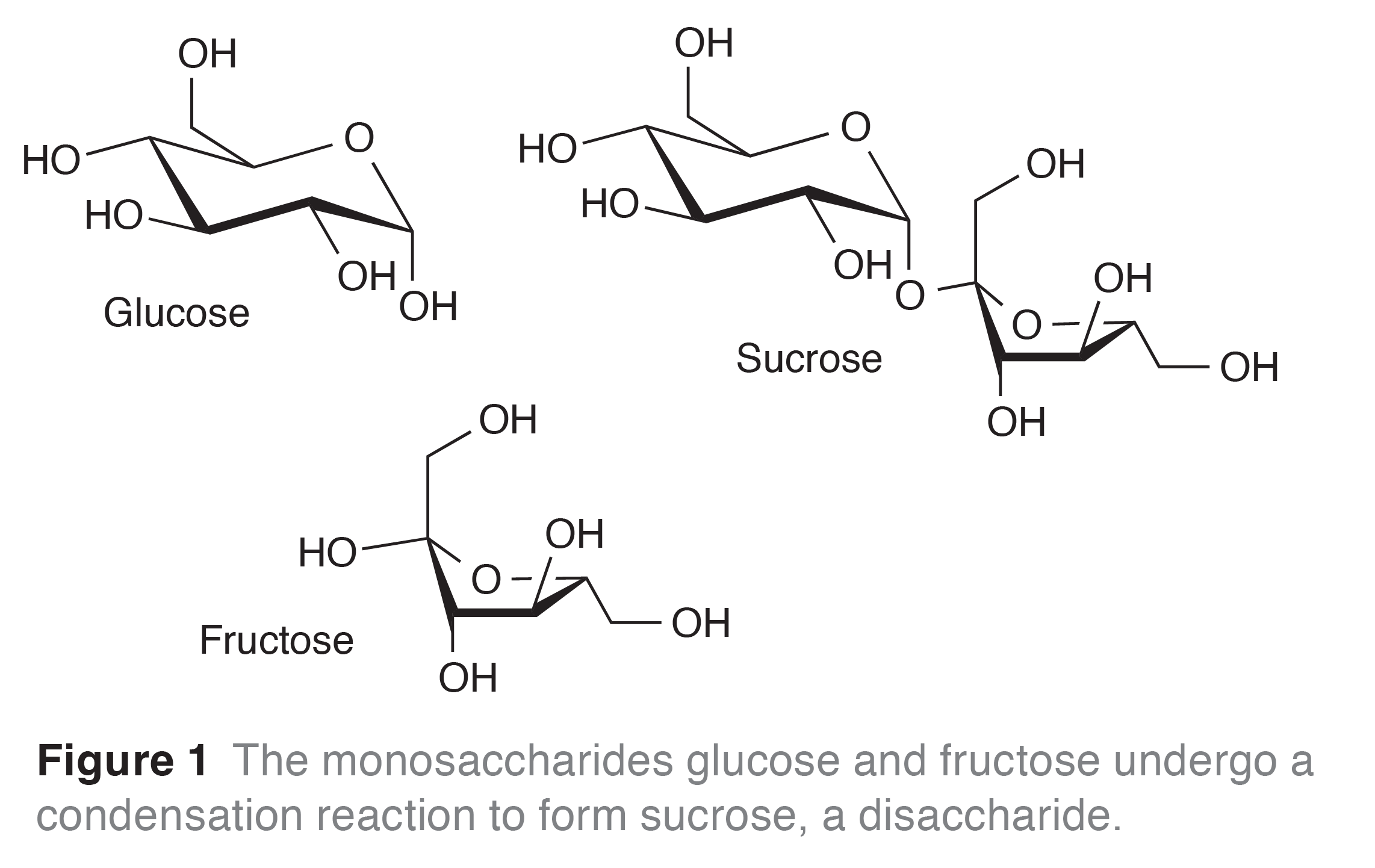

Sugars play a vital role in sweet chemistry, and most often come in the form of monosaccharides, e.g. glucose and fructose, or disaccharides, e.g. sucrose, (see Figure 1).

Have you ever considered the chemistry going on when you eat a sweet? Sweets have been around for centuries (Box 1). Not only do they have to taste good, but the way in which the ingredients react in your mouth provide many of the pleasurable sensations involved in eating them. This article aims to explain the ways popular sweets work.

Sherbet fountains

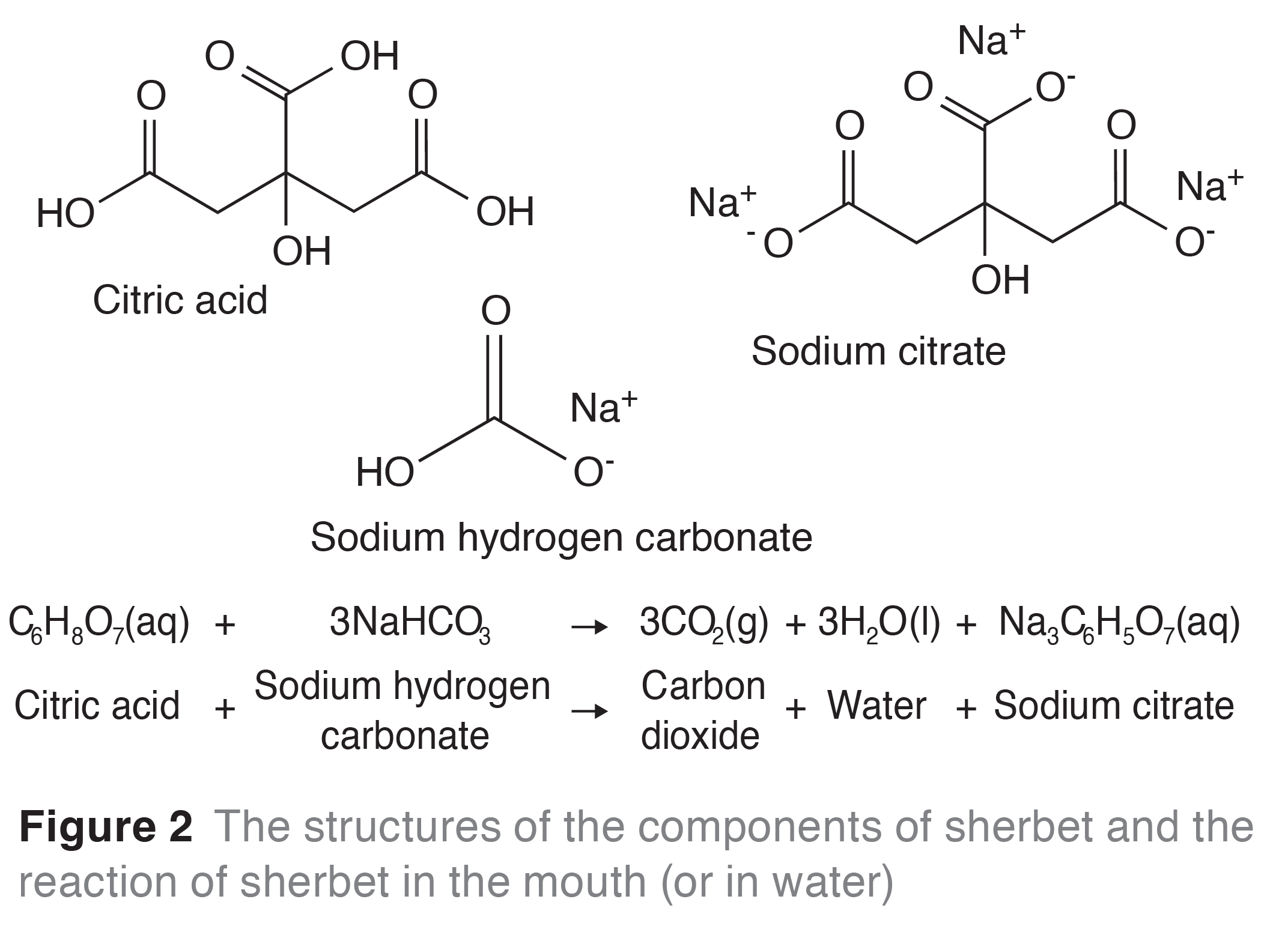

The sherbet fountain is a popular traditional sweet. It is composed of a liquorice stick and a crystalline powder (sherbet). Sherbet is made from citric acid and sodium hydrogen carbonate (bicarbonate of soda). This powder gives rise to a fizzing sensation in the mouth, as the saliva in the mouth provides a watery medium for a reaction to occur as the citric acid and bicarbonate of soda (a base) dissolve. The reaction of an acid with a carbonate releases carbon dioxide, water and a salt (in this case sodium citrate, Figure 2).

Other ingredients such as icing sugar are also added to the powdery mixture to give the sherbet a sweet taste, blending with the sourness of the citric acid and salty/soapy taste of the bicarbonate of soda. The confectioner may add other flavourings as well to give an individual taste to the powder.

Many of the experiments chemists deal with in the laboratory are exothermic, i.e. they give out heat to the surroundings. However, the reaction between citric acid and bicarbonate of soda is endothermic, i.e. heat is absorbed from the surroundings. This means that when you eat sherbet the temperature in your mouth drops, as heat is absorbed by the reaction—so eating sherbet feels cool.

A brief history of sweets

Up to the early 1800s sweets were a handmade delicacy, requiring skill and practice to perfect. Sweets used to have rich, pungent flavours, much more than they do today due to the individual craftsmanship. It was only as industrial methods developed that they began to be made in high quantities, with reduced quality and care. The first ever ‘sweet’ was honey, which was used as far back as prehistoric times.

In Tudor times those who could afford luxuries enjoyed the likes of jellied fruit, marzipan, gingerbread and sugared almonds. This was all before the introduction of chocolate bars in the mid-nineteenth century, a time when many sweet and chocolate factories were founded, including Cadbury, Fry’s and Rowntree’s. With the advent of the sweet industry, confectionery was made on a larger scale.

Hard-crack sweets were common and are still made the same way today by specialist traditional confectioners. The thick, coloured, flavoured sugar syrup is moulded by hand, while being warmed to ensure an even distribution of temperature. It is then extruded to the right diameter, chopped into the right-size pieces and cooled to form a hard, solid sweet. Sticks of rock are an example of hard-crack sweets and are famous for having lettering or pictures running through the length of the stick. Large versions of the letters or images are formed from layers of coloured, soft, warm candy then enclosed into a roll, which is pulled out to the right diameter before the candy sets hard.

Popping candy

Popping candy pops in your mouth, giving rise to its unique sensation on the tongue as it cracks and snaps. The ingredients of popping candy are similar to many other sweets: sugar, corn syrup and flavourings. These are mixed together with some water and heated, boiling off all of the water present, leaving a thick, syrupy residue.

The resulting syrup is pressurised to around 41 atmospheres (~4MPa) with carbon dioxide gas, bubbles of which become trapped in the syrup. When the mixture is cooled (still under pressure) it hardens and becomes brittle. On releasing the pressure, the larger bubbles of trapped pressurised carbon dioxide cause the candy to shatter into small pieces.

These fragments contain tiny bubbles of pressurised carbon dioxide. When the brittle candy is dissolved in the mouth, the trapped bubbles of pressurised carbon dioxide are released with snaps and pops in your mouth.

After-dinner mints

Have you ever eaten an after-dinner mint and wondered how the gooey, liquid fondant centre is coated with chocolate while retaining a perfect shape? One method of making soft- or liquid-centred chocolates is to inject the filling into the chocolate shell and seal the hole with more chocolate. But there are no holes to be seen on an after dinner mint, so how do they do it?

The fondant centre is composed of water, sugar, mint flavouring and invertase. Invertase (more correctly called α-D-glucosidase) is an enzyme that hydrolyses the disaccharide into two monosaccharides: fructose and glucose (Figure 1).

Initially the fondant centre is very firm and can be coated with chocolate. The mints are then stored at room temperature for 3 days, and this is when invertase gets to work. All of the sucrose is converted into fructose and glucose. As these monosaccharides are smaller molecules than sucrose, they pass over one another with ease, giving a more fluid-like consistency. Now the chocolates are ready to be boxed up and sold as after-dinner mints.

Fudge

When sugar dissolves in water, a sugar syrup is formed. The degree to which the sugar dissolves increases as the temperature increases, meaning that the greater the temperature the higher the concentration of sugar it is possible to dissolve. When this sugar syrup is cooled it becomes super saturated, in other words the amount of sugar stored in the solution is greater than its limit at that temperature. The objective at this stage is to prevent the sugar crystallising out of the solution, which can easily happen because a super-saturated solution is unstable and a slight knock can initiate crystallisation.

Different types of sweets require the syrup to be heated to different temperatures. The temperature the solution is heated to dictates the sugar concentration of the resulting type of sweet. Table 1 provides a guide as to which sweets are made with different concentrations of sugar in the syrup.

Higher concentrations of sugar result from increasing cooking temperatures, so producing different types of sweets. The sugar stage up to 154°C is determined by dropping a small sample of the hot mixture into a bowl of cold water. The stage names describe the appearance or feel of the resulting blob of cooled, sugary mixture. Above 160°C the sugar begins to melt and decompose, giving rise to an increasingly dark liquid.

There are two different categories of sweets: crystalline and non-crystalline. Fudge and fondants are types of crystalline sweets. A boiled sweet is an example of a non-crystalline sweet—it is a glass, having an irregular amorphous structure. Crystalline sweets indicate that when the hot sugar syrup was cooled, the sugar molecules crystallised out to form the sweet. In a crystal the molecules fit together in an ordered pattern. Small sugar crystals give rise to the grainy texture of fudge.

To prevent unwanted sugar crystals forming when making non-crystalline sweets, you can employ various tricks. You can use corn syrup, which is a solution of maltose (a disaccharide of two glucose units) and some longer chains of sugars (oligosaccharides) produced through the hydrolysis of starch. The oligosaccharides are large molecules that hinder the sugars from crystallising. Butter fats also have this property of preventing crystallisation, getting in the way of the interlocking sugar molecules. The smooth texture of toffee is owed to plenty of butter.

An understanding of the subtleties of sugar chemistry and a little culinary flair can lead to sweet success. Such knowledge can also lead to a greater appreciation of the craft of the confectioner.

Further reading

I took inspiration for this article after performing some of Dr Joanna Buckley’s ‘Edible Experiments’, a series of food-based chemistry resources.

Glossary

Carbohydrates. The most abundant class of biological molecules. They are composed of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen based on the general formula Cx(H2O)y. The simplest carbohydrates are the sugars.

Condensation reaction. The combining of two molecules with the loss of a small molecule (e.g. water).

Disaccharide. A sugar formed by the condensation of two monosaccharides (which may be the same or different), e.g. sucrose (C12H22O11) is made from glucose and fructose.

Enzyme. A specific type of protein that acts as a biological catalyst, speeding up a chemical reaction while remaining unchanged itself. Enzyme names are denoted by the suffix -ase.

Monosaccharide. A sugar (carbohydrate) with an empirical formula (CnH2nOn) where n = 3–9. Glucose and fructose are examples of six-carbon monosaccharides.

Oligosaccharide. A carbohydrate formed by the condensation of a small number (three to ten) of monosaccharides.

Starch. A polysaccharide found in plants. It is a polymer formed by the condensation of many glucose molecules.